The Power of Storytelling and How it Affects Your Brain

Once upon a time there was a young man who worked in a museum. Each day the young man would study the precious relics around him and wonder what they were, where they had come from, and who they were created for.

The oldest story in the world: The Epic of Gilgamesh

Amazing as they were, there were still a small number of relics so mysterious that all he could do was look on in fascination. They were stone tablets many thousands of years old and from thousands of miles away. On them were strange and ancient markings that no-one could understand.

To unravel the mystery the young man decided to work hard and study languages so old they were no longer spoken. Languages once used by people in far-off places whose bones were long since dust in the earth.

Finally, more than two decades after the tablets had first arrived at the museum, the young man successfully managed to crack their mystifying code. For the first time in over two thousand years the tablets found a new reader and what they revealed to him was the world’s oldest recorded story.

From Stone Tablets to Podcasts

The young man who decoded the tablets’ puzzle was an English archaeologist named George Smith and the story he unearthed was The Epic of Gilgamesh – an ancient Mesopotamian poem written sometime around 2100 BC.

Despite the date and place of its origin, the Gilgamesh epic showcases many of the same elements and themes still present in the stories enjoyed today by modern readers – a hero embarks on a difficult journey in which there is romance and seduction, encounters with strange and exotic characters, impossible obstacles to overcome, and a final redemptive character arc.

The similarities between old stories and newer ones are no coincidence. Time does not seem to matter much to themes; nor indeed does location.

The Princess and the Frog. Illustration by Warwick Goble.

A 2006 analysis of 90 folktale collections from around the world (from both tribal societies and industrialised ones) reveals as much, with scholars describing the presence of a number of distinctly common narratives covering basic human needs and desires in the stories they examined.

For journalist and author Christopher Booker, there are just seven of these universal plots, and they can be seen to return time and again in books, television programmes, movies and even podcasts. They are:

- Overcoming the monster - Beowulf, War of the Worlds

- Rags to riches - Cinderella, Jane Eyre, Pretty Woman

- The quest - The Iliad, Lord of the Rings, Star Wars, Serial

- Voyage and return - Alice in Wonderland, Toy Story, Where the Wild Things Are, The Little Prince

- Rebirth - Sleeping Beauty, A Christmas Carol, The Shawshank Redemption

- Comedy - A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Four Weddings and a Funeral

- Tragedy - Hamlet, The Godfather

Though stories often differ wildly in a rich variety of ways, Booker believes that almost all can still be simplified to a core theme that fit neatly into one of the categories outlined above.

The voyage and return narrative is perfectly exemplified in Alice in Wonderland. Illustration by Arthur Rackham.

This has nothing to do with a lack of invention on the part of the writer though. The commonalities in stories around the world merely express shared human impulses, thoughts, fears and aspirations.

“Stories have always been a primal form of communication,” says psychologist Pamela Rutledge. “They are timeless links to ancient traditions, legends, archetypes, myths, and symbols. They connect us to a larger self and universal truths.”

‘What’s the Story?’ How Stories Help Us Understand the World

Not only do stories connect us to the past and express universal beliefs, they can also help us develop a better understanding of the world and those we share it with. This is part of the reason why your brain loves stories.

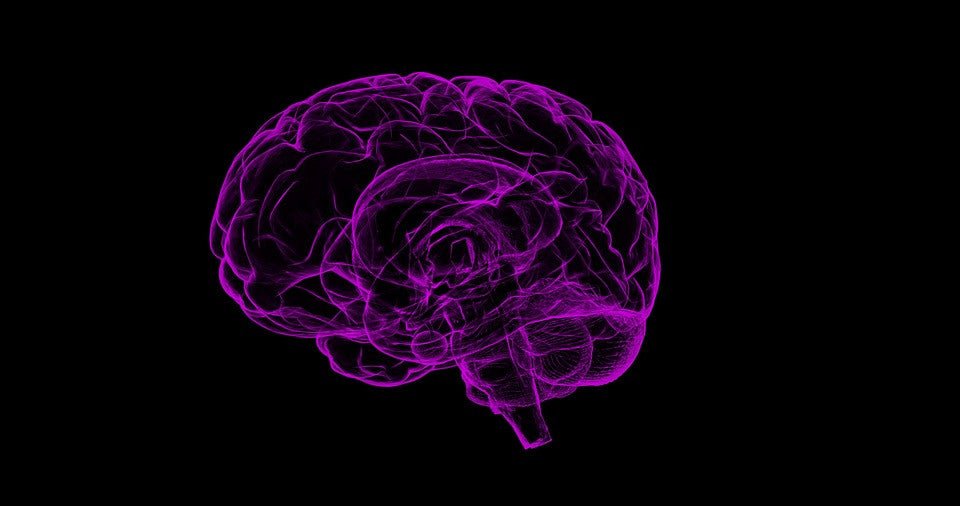

With around a hundred billion neurons and almost a quadrillion connections between the neurons your brain is an extraordinarily complex organism – so complex, in fact, it borders on the wondrous.

Yet it is still a pattern-seeking instrument that looks to put the chaos of the world into some kind of recognisable order. Stories represent our most powerful and meaningful way of doing just that.

From bedsides to firesides, we regularly use stories to relay our experiences and connect with those of the people around us. We use them to explain events, examine our values and explore notions of meaning and purpose.In this sense, stories offer a perfect common ground for reflection. What makes this common ground all the more precious is that it gives us a glimpse into the lives of others and the everyday situations and struggles they face.

This “peeking” into another life through a story is possible in any number of ways – it could be when you read a book, watch a movie or talk with a friend. Whatever their form, stories are a constant in our lives.

In fact it’s estimated that as much as 65 per cent of all human interactions take the form of social storytelling (i.e. gossip). And where there are stories, there is greater potential for empathy and discovery. As Rutledge puts it: “When you listen to stories and understand them, you experience the exact same brain pattern as the person telling the story.”

Storytelling has been an important tool for social cohesion for millenia.

So by imagining ourselves in someone else’s position we can either affirm or challenge our beliefs and assumptions. Indeed, according to psychology researcher Dan Johnson, simply reading fiction can increase our empathy towards others we may have initially viewed as being “outsiders”.

This is in agreement with the findings of another study published in Science magazine that fiction “uniquely engages the psychological processes needed to gain access to characters’ subjective experiences.” One alluring implication of this is that our personal stories are therefore never complete; they’re part of a narrative that continually evolves as we try see the world from multiple points of view.

The Power to Imagine New Worlds

There is widespread discussion today about the potential for technology to transport us to new places, with virtual reality a particularly good example.

Yet technology too relies on stories since a good plot and credible characters are essential to deep engagement. It’s even reasonable to suggest that stories are in fact the original virtual reality, since they allow us to experience other places, characters, events and consequences purely by stimulating our imaginations.

As Rutledge puts it “To the human brain, imagined experiences are processed the same as real experiences... Through imagination, we tap into creativity that is the foundation of innovation, self-discovery and change.”

Psychologists refer to this flight of imagination as “narrative transport”. It occurs when we are fully immersed in a story’s world. It’s understood that the greater the level of empathy in the reader, the deeper the transportation experience becomes.

But what is actually happening in the brain as it engages with stories?

The Science Behind How Stories Affect Your Brain

Listening to a story that’s being told or read to you activates the auditory cortex of your brain. Engaging with a story also fires up your left temporal cortex, the region that is receptive to language. This part of your brain is also capable of filtering out “noise”; that is, overused words or clichés. That is why the most skilled storytellers are careful about the language they use, employing a host of literary techniques to keep your brain engaged.

And once it is, other regions soon begin to participate in the process.

For instance, once you begin to feel some kind of emotional engagement with a story it is because the frontal and parietal cortices have been stimulated. Powerful descriptions of food, for example, will also stir up your sensory cortex while descriptions of motion or action will get a response from the central sulcus, the primary sensory motor region of your brain. Indeed, just thinking about running can activate the neurons associated with the act.

Research also shows that all this brain activity can last for several days, explaining why good stories tend to stay with us. Additionally, stories also improve our ability to recall any information embedded in them. One estimate suggests that we can recall facts up to 22 times more effectively when they are part of a story rather than just isolated data. Thus you are much more likely to remember the story of Gilgamesh’s discovery from earlier on than just the facts of the discovery alone.

All this mental activity can also bring about changes in your body. During scenes of high action or tension, the stress hormone cortisol is released into your bloodstream, which leads to greater immersion and responsiveness to the arc of a story.

More character-driven stories will affect the release of oxytocin into the blood, a so-called “empathy” hormone that helps people bond. It is, in fact, the same hormone that's released into the bloodstream of breastfeeding mothers.

Making Childhood Connections

As we’ve seen, the huge role that stories play in our social interactions and views is universal. Their formative impact also begins very early in life.

In just their second year, children have already begun to understand basic concepts (discussed in another blog here). However, they will not hold on to most of their earlier memories because they have no context on which to anchor them.

This changes as soon as a child begins to develop narrative skills. These will give him or her a better mechanism for making sense of the world around them. By the age of four or five a child will also have developed what’s known as “theory of mind”. Essentially this relates to their ability put themselves in another’s shoes, or to be aware of their awareness.

This rapid mental evolution can be seen in a 2007 study by psychologists at the University of Waterloo in Ontario in which researchers found that while three-year-olds were unable to follow the thoughts of an imaginary character (a farmer looking to milk his cows), the five-year-olds in the study were able to do so.

The adventures and characters that children experience through stories are almost certain to have a lifelong impact. This then is a pivotal time in their development, not just in terms of vocabulary or reading skills, but in the broader terms of their ability to think, empathise and imagine.

Find stories worth sharing by browsing our carefully curated selection of books.